The dangerous rise of drug sniffing dogs

By Núria Calzada

Araceli was having a coffee on a terrace when a police dog marked her. Seventy-two-year-old Laura was getting off the bus when another dog marked her at the station. Alberto was on vacation with his family when at a roadblock the canine unit marked his vehicle. Pablo, one of the teachers on the end-of-year trip, was marked by a police dog on his way to the beach.

When a police dog marks you as a carrier of unregulated drugs, it not only leads an officer to believe there is sufficient evidence to search you, but also exposes your privacy and personal life to passersby and anyone accompanying you. These dogs are trained to detect certain drugs, but they do not differentiate between contexts and are unaware of the harm their alerts may cause.

Araceli uses cannabis and, although she wasn’t carrying anything, she was searched in public—to the bewilderment of those on the terrace and, worse, to the shocked and horrified gaze of her teenage son, who happened to be riding by on a scooter. Laura, who uses cannabis therapeutically, had four buds confiscated and was fined for illegal possession. Even after a reduction, the 300-euro fine was a heavy burden on her widow's pension. Alberto does not consume drugs and still cannot explain why the dog marked his car; his daughters were terrified. Pablo, a teacher with over twenty years at his school and a good reputation among staff, families, and students, also had nothing on him. Still, he had to provide explanations and faced rejection and public shaming upon return. His life at school has never been the same. These are just some of the serious consequences people face when a detection dog targets them.

Canine units, known as K9s, are booming in police forces across Spain. In addition to the National Police, Guardia Civil, Mossos d'Esquadra, and Ertzaintza, many municipalities are now adding detection dogs to their local police units. This growing interest has led to the organization of professional events, such as the First Championship of Substance Detection Dogs (Vila-real, 2015), the First Conference of Citizen Protection Dogs in the Local Police (Los Barrios, 2016), the First National Distinctions for Guides, Dogs, and Police Canine Units (2018), the First Campus of Canine Units of Local Police of Catalonia (Cornellà, 2018), and the First National Conference of Canine Guides (Salou, 2021).

In any case, it seems that the incorporation of canine patrols in cities and municipalities in Spain is a growing phenomenon and, precisely for this reason, it is worth asking what data support their use and why local councils are embracing this measure with such enthusiasm.

Where do these furry agents come from?

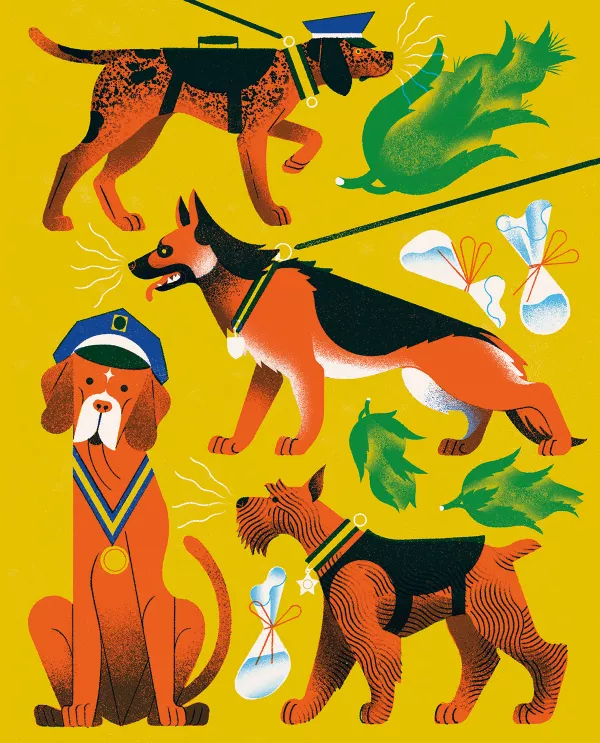

The first canine units in local Spanish police forces appeared in the 1970s and 80s, initially focused on substance detection, which at the time was considered primarily a public health concern with implications for public safety. Until recently, most units rented or purchased dogs from breeders or training centers, often at high cost. In recent years, however, there has been a push to incorporate adopted dogs from shelters, municipal kennels, or even private listings online. Certain breeds are generally preferred due to their aptitude for detection work, including Belgian Malinois, German Shepherds, and Labradors. Unlike the National Police, Guardia Civil, or Mossos d'Esquadra, dogs used by local police forces are often not owned by the administration, but by the officers themselves. There is typically no centralized selection or screening process. Instead, each officer selects and trains their dog individually.

Currently, most municipalities sign “free assignment” agreements with officer-dog owners, agreeing to cover maintenance, training, and liability insurance costs. These costs vary significantly—from €1,100 annually in Polinyà to up to €4,000 in Matadepera, both in the province of Barcelona. Some municipalities, however, contract private companies to provide canine detection services, either sporadically or on a regular basis. The legitimacy of this outsourcing is questionable, as Spanish administrative law generally prohibits delegating sanctioning powers to private entities—a point upheld in various court rulings, such as those concerning labs conducting confirmatory drug tests (Perea, 2020).

And what happens to these dogs when they retire? After about eight or nine years, when age-related decline sets in, dogs are typically retired. If the dog is owned by an officer, it stays with them. If owned by the municipality, it is usually entrusted to its handler or offered for adoption if that isn’t possible.

No, They’re Not Addicts: Limpet Marking.

Far from urban legends that claim that they train dogs by hooking them to certain substances, the truth is that they are trained to identify substances and mark where they are in exchange for a reward, which is not any substance to calm their abstinence, but something much more innocent like playing with a ball, a roller or a teether. In fact, since these are controlled substances, they must obtain authorization from a judge to request them for the purpose of training, and sometimes, due to the difficulty of obtaining it, they opt to train with synthetic scents or pseudoaromas, a method that many guides question. Another common doubt is how many substances they are capable of detecting. There is also a misconception that dogs can detect only one substance. In reality, they are usually trained to recognize several. Dogs are generally specialized in one category (drugs, explosives, fire accelerants, or currency), but within that category, they can identify multiple substances.

On the other hand, marking is the way in which the dog is trained to indicate detection. In active marking, the dog may bark or scratch to signal the source of the scent. In passive marking, the dog will sit or focus its nose on the target area—a useful technique for avoiding damage, especially when searching people or vehicles. Among the passive marking methods, the most recent and apparently booming system is the so-called "limpet marking", a method patented by Javier Macho, technical coordinator and instructor of the Local Police Canine Unit of Burgos, Spain's first such unit. According to Macho, in limpet marking, whthe dog "sticks" its nose to the exact location of the detected substance. If it can’t reach the area, it may sit, lie down, or point its nose in the correct direction. This approach is particularly useful in detecting small quantities hidden in clothing or intimate areas. According to Macho, "It tells us exactly where they are carrying it.". In other words, These dogs are not trained to detect large-scale drug caches, which is typically the domain of the National Police or Guardia Civil. Instead, they are used in minor possession cases, where the quantity is small enough to evade standard searches. Other cited benefits include reducing the need for intrusive searches and addressing cases when a same-sex officer isn’t available to conduct a pat-down. This is the system that is arousing passions and is present in most of the autonomous communities.

It is ironic that current canine training is still based on Pavlov's early 20th century classical conditioning methods, while Pavlov warned that the only stimuli he found difficult to apply with any reliable predictive value were odors (Marks, 2009): "It has been extremely difficult, if not impossible up to the present, to obtain the same accuracy in grading olfactory stimuli as any other stimulus. It is also impossible to limit the action of olfactory stimuli to an exact time period. Moreover, we know of no subjective or objective criteria by which small variations in odor intensity can be determined."

No official training.

The Guardia Civil has a dedicated K9 division known as the Cinological and Remote Service (SECIR), while the National Police has operated its Canine Training School since 1975, offering official drug detection training. The Mossos d’Esquadra require prospective canine officers to pass a competitive exam and complete a six-month course at the Institute of Public Security of Catalonia. In short, these three forces have formal, standardized programs that ensure a minimum level of training quality and consistency.

In contrast, the training of local police officers is far less regulated and largely dependent on the availability of official training in their autonomous community. In most cases, there is no specific program, or only a limited number of spots available. As a result, many local officers turn to private companies for training. Who certifies these courses? In most cases, no one. Some training centers are accredited by the Certification Council for Dog Trainers of the National Association of Professional Dog Trainers (ANACP), which obliges them to adhere to a code of ethics and guarantees a certain standard of service. But these are open-enrollment schools for the general public and are not overseen by any official policing body. The result is a complete lack of oversight.

Training programs can vary widely in content, price, number of hours, format, and methodology. Unlike private security firms that train dogs for explosives detection—who must be certified by the State Aviation Safety Agency (AESA)—there is no equivalent system for drug detection dogs in Spain.

A practice exempt from regulation.

To date, Australia is the only country with specific legislation regulating the use of drug detection dogs. Its Drug Detection Dogs Act 2001 authorizes police to conduct searches in public places without a warrant based solely on a canine alert.

In Europe, between 1999 and 2003, Interpol created the European Working Group on the Use of Police Dogs in Crime Investigation (IEWGPR) with the goal of standardizing working guidelines across member states. However, no final document or binding framework was ever published.

In the United Kingdom, the only available guideline is the ACPO Police Dog Care and Training Manual, which is not legally binding. In the United States, regulation varies by state, generally falling under POST (Police Officer Standards and Training) agencies. In addition, the Scientific Working Group on Dog and Orthogonal Detector Guidelines (SWGDOG) has released voluntary best practices for detection dog use and training.

Spain, by contrast, lacks any form of specific regulation. There are no laws or official documents addressing key issues such as accreditation of canine training schools, standardized training protocols for dogs and handlers, certification criteria or quality standards, defined working hours and conditions for dogs, authorized areas of deployment and welfare oversight or post-retirement arrangements. Until very recently, police dogs in Spain were considered no different from other law enforcement equipment—on par with a firearm, a pair of boots, or a radio. It wasn’t until January 2022 that animals were legally recognized as sentient beings under Spanish law.

However, even with this recognition, Spain’s Citizen Security Law and related legislation still fail to define detection dogs as agents of authority. This legal void has real consequences: in cities like Pamplona or Valencia, individuals who attacked police dogs after being marked were prosecuted for animal abuse, not for assaulting an officer. Equally concerning is the absence of any regulation requiring regular evaluation or re-certification of detection dogs to ensure that they remain fit for operational service.

Perhaps because of all these legal gaps, Spain’s conservative Partido Popular submitted a non-legislative proposal in 2021 urging the government to develop comprehensive regulations governing the use of detection dogs—not only within the State Security Forces and Corps but also among civilian organizations offering canine services.

So, what does it actually take to create a canine unit in a municipality? In practice, very little: usually, all that’s needed is a local police officer who is passionate about dogs, who personally pays for acquiring an animal (without any official screening or evaluation), completes private handler training (without government approval), and gains the support of their police chief and the town’s mayor. This arbitrary, discretionary process clearly violates basic legal principles such as legality, legal certainty, and equality before the law, all of which are protected under the Spanish legal system.

The myth of the infallible dog.

It’s indisputable that dogs have a far superior sense of smell compared to humans. However, they are far from infallible. The myth of the "infallible dog" is so deeply ingrained in our society that it often escapes rational scrutiny. And it is precisely this myth—and the lack of critical oversight—that has led to the unchecked proliferation of canine units, without proper debate or analysis of their accuracy, effectiveness, or impact on citizens.

This is perhaps the most critical question, and yet, to our knowledge, there are no published data in Spain to justify the use of drug detection dogs on public streets—let alone to assess their social impact. It is essential to determine how often dogs correctly identify substances and how often they produce false positives, which can have deeply harmful consequences. Despite bold claims by police about dogs’ “supernatural” sense of smell, the scientific evidence tells a different story.

Although there is no universally accepted standard for measuring detection accuracy, many experts suggest a minimum acceptable effectiveness rate of 90%. A 2014 Polish study (Jezierski et al.) found that dogs operating in training environments correctly indicated the presence of drugs in 83% of cases involving enclosed spaces. However, accuracy dropped significantly in real-world contexts, such as searching vehicles or open areas, with success rates of 63.5% and 57.9%, respectively.

As other researchers have noted (Cooper, 2014), performance dramatically declines when dogs are taken out of controlled training environments and placed in field conditions: accuracy rates can fall from 99% to just 43%. This concern has sparked considerable debate in Australia, where New South Wales (NSW) became the first state to use drug-sniffing dogs as a public policing strategy in 2002. Under the Detector Dogs Act, the NSW Ombudsman was tasked with reviewing the program during its first two years. His 2006 report found no evidence supporting the use of drug detection dogs and identified major issues—most notably, that drugs were found in only 26% of searches. That meant thousands of people had been publicly searched without any substances being found.

Police responded by claiming that some false positives could be explained by residual drug odors—individuals who had used or been near someone who used drugs. The Ombudsman’s report noted that 59% of people who were falsely flagged admitted to such contact. Still, a large percentage of cases remained unexplained, and in any case, the justification was insufficient to explain the 7,497 individuals who were searched in public without any drugs being discovered.

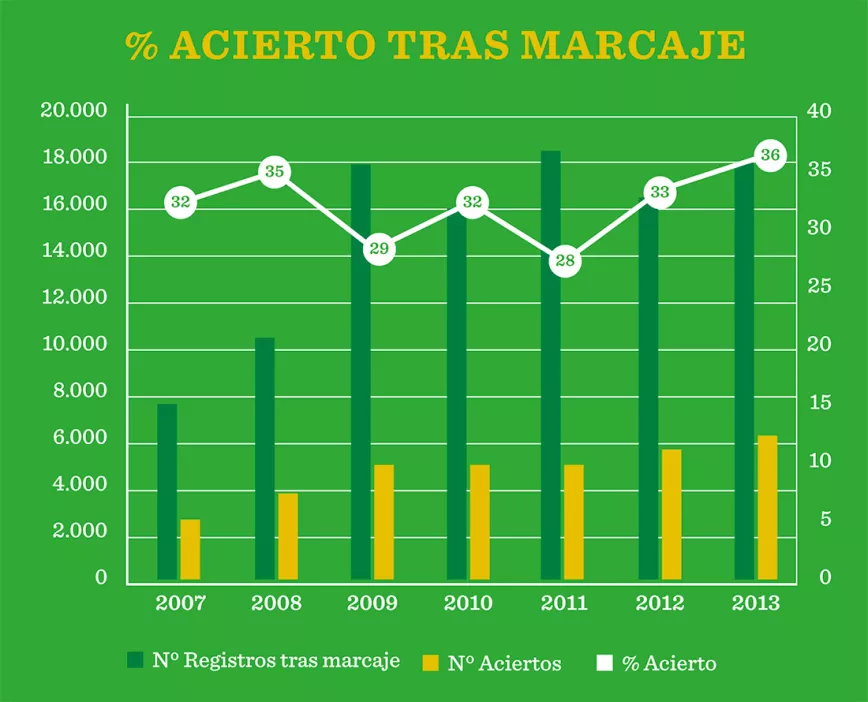

Further data provided by Greens MP David Shoebridge showed that between 2007 and 2013, a total of 103,476 searches were conducted in Sydney based on dog alerts. In only 33,105 of those cases were drugs actually found—an average success rate of just 32%. Year by year, this figure fluctuated between 29% and 36%, maintaining consistently low accuracy. A subsequent review covering 2008 to 2018 (Agnew-Pauley & Hughes, 2019) reached similar conclusions: only about one in three individuals searched after a canine alert was found to have drugs. Even less encouraging are the results from the British Transport Police during the 2008 Latitude Festival in Ipswich, where only 12% of searches following dog alerts revealed unregulated substances.

In any case, even if we accept that drug odor residue might trigger some alerts, it is important to emphasize that merely carrying the scent of a substance is not a crime. This brings us to a critical flaw in the practice of using drug detection dogs—especially in countries where therapeutic and/or recreational cannabis use has been legalized or decriminalized. In fact, several U.S. states have debated whether legal cannabis will require retraining or even retiring drug-sniffing dogs, sparking controversy either way.

On the other hand, in addition to the lack of clear standards defining successful performance, other factors also affect canine detection accuracy. These include the type of drug (cannabis and amphetamines are easier to detect than heroin), the breed (German Shepherds tend to be more accurate, while Terriers perform less reliably), the dog’s age, the number of distractions, weather conditions, the search location, and the number of hours worked.

There is also controversy regarding the role of handlers. The Chicago Tribune analyzed three years of data from local police departments and found that only 44% of alerts led to the discovery of drugs or paraphernalia. But when suspects were Hispanic, the success rate dropped to just 27%.

One explanation comes from a study conducted at the University of California, Davis, which found that dogs often respond to cues from their handlers. In the study, fourteen dogs were tested for their ability to find hidden substances. However, their handlers were misled into believing that certain areas contained drugs, even though they did not. Remarkably, the dogs still “alerted” in those areas, especially where the researchers had suggested drugs might be found. In short, the handlers—often unconsciously—directed the dogs’ behavior. This study, led by researcher Lisa Lit, was so controversial that dog trainers and law enforcement handlers heavily criticized it and refused to collaborate on further research. Years later, Lit admitted in an interview that the backlash had effectively ended her career.

The canine sense of smell as a rational clue.

According to Spain’s Citizen Security Law 4/2015, the illicit use or possession of narcotic substances is considered a serious offense (Article 36). The law also stipulates that identification, verification, and searches in public spaces may be conducted when there are indications that a person may have committed an infraction or crime. Specifically, external and superficial body searches may be carried out “when there are reasonable indications to believe that it may lead to the discovery of instruments, effects, or other objects relevant to the investigative or preventive functions legally entrusted to law enforcement.”

There’s no doubt that being subjected to a search constitutes an act of criminalization and public shaming, often at great cost to the individual’s privacy and dignity. Because canine alerts typically occur in public, most people are searched in full view, triggering emotions like embarrassment, humiliation, or anger—especially when the alert proves to be a false positive.

In practice, police officers consider a dog’s alert as sufficient rational grounds to justify a search. But is a sniff truly a “rational indication”? First, it is important to note that Spain’s Public Security Law does not explicitly mention canine units as a valid method for substance detection, nor does it formally recognize their alerts as rational indicators. Secondly, a dog’s alert is not considered valid evidence in Spain’s criminal justice system.

In forensic contexts, scent detection—also known as forensic odorology—is a highly specialized method in which trained dogs identify individuals by comparing scent samples collected at a crime scene with samples taken from suspects. This practice, common in the United States since the 1920s, has led to thousands of convictions for robbery, rape, and even murder, sometimes based solely on a dog’s identification. Some of these cases have resulted in life sentences or even the death penalty. The myth of the infallible dog is so pervasive that even the courts have often failed to critically assess its reliability—treating scent detection as unquestionable, unlike other types of forensic evidence. Yet in Spain, a dog’s sniff is not admissible in the criminal realm. So why is it accepted in administrative contexts, which have lower evidentiary standards but can still seriously affect people’s lives?

Finally, in order to establish the rational justification of the search, it is necessary to evaluate, on the one hand, the concurrence of indications, rational indications or suspicions and, on the other hand, the necessity, opportunity and proportionality of the search. Therefore, the officer must assess on a case-by-case basis the opportunity to perform the search, taking into account various circumstances, such as the seriousness, the type of crime, age, time and place of detention (it is not the same to proceed to a search in a quiet place than in a crowded area) and the presence of third parties in the place of the search, which may affect their privacy or reputation.

A dog’s olfactory reaction, however, is a learned behavior based on classical stimulus–response conditioning. It does not consider the broader legal or contextual elements required by law, and should never serve as the sole basis for identification and search. Therefore, searches prompted solely by a police dog’s alert represent an illegitimate and unnecessary intrusion into an individual’s right to privacy. This right, legally understood as the individual’s ability to decide when, how, and to what extent personal information is disclosed, is critical to preserving social relationships, reputation, and mental well-being. A canine alert, devoid of nuance and legal rigor, can have severe consequences in both the public and private spheres.

Given that drug-sniffing dogs frequently produce false positives, cannot distinguish between the multiplicity of possible situations, and that their marking is a violation of civil rights, their use in justifying searches should be considered arbitrary. Such actions, lacking legal indicators and individualized suspicion, are contrary to the standards of the European Court of Human Rights. As legal scholar Amber Marks, director of the Criminal Justice Centre at the University of London, has argued, dog-based searches may violate Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights. This article guarantees the right to privacy and states that any interference must be in accordance with the law (principle of legality), pursue a legitimate aim (such as crime prevention), and represent a necessary and proportionate response (principle of proportionality). Dog alerts, on their own, often fail all three tests.

Collecting zeal.

Given that the deployment and expansion of canine units lack a solid evidentiary foundation and pose clear risks to civil liberties, we must ask: why are these units spreading so rapidly across Spain? The answer may lie in their efficiency—not as tools for justice, but as tools for revenue collection. Limpet marking, the method most commonly used, is specifically designed to detect small quantities of substances. Four-legged agents are more effective, faster, and cheaper than human officers when it comes to identifying people in possession of drugs. Thus, the growth of local police canine units seems driven more by financial incentives than by genuine public safety concerns. Far from achieving their stated goal of combating drug trafficking, these units have become ideal mechanisms for extracting fines from citizens—often at the expense of their rights.

Actually, Spain imposes 43% of all cannabis-related fines in Europe (El Público, 2022), making it the leading country in terms of sanctions, even though it ranks only third in consumption (EMCDDA, 2022). It’s reasonable to assume that the proliferation of canine units has contributed to this discrepancy. The media has highlighted their role in increasing drug-related sanctions:

- In Altea, the local police reported a 20% increase in possession and consumption cases since introducing a canine unit (Las Provincias, 2021)).

- In Sant Andreu, drug seizures reportedly rose by 80% (TV3, 2014).

- In Paterna, actions related to possession and consumption increased by a staggering 220% (Paterna, 2015).

These successes are celebrated by police officers and local officials. Santi Ferrer, canine handler for the Cornellà local police, noted that “canine units are becoming more important every day” (El Periódico, 2018). The mayor of the same municipality, Antonio Balmón, called them “a godsend” (La Vanguardia, 2022). Joan Bou of the Girona Municipal Police attributed a 19% increase in drug-related fines in 2016 to the new canine unit (Emporda.info, 2017). Even when officials insist that the goal isn’t revenue collection, the numbers speak for themselves. Arnau Rovira, city councillor for citizen security in Manlleu, claimed, “the function is not to collect fines,” despite headlines like: “New police dog issues 22 drug fines in just two days” (Manlleu, 2022).

It's also worth noting that Law 4/2015 eliminated a key provision from the earlier Law 1/1992, which allowed for suspension of fines if the individual agreed to undergo treatment. That earlier law reflected a more rehabilitative and resocializing approach. The current law, by contrast, leans toward punitive and financial objectives.

This underscores one of the core problems with using drug detection dogs: as long as the effectiveness of police work continues to be measured in superficial metrics—such as the number of sanctions issued, the amount collected, the number of arrests, or the quantity of drugs seized—rather than in meaningful indicators like reduced harm, improved public health, or lower crime rates, little progress will be made.

Have these so-called “successes” disrupted drug markets? Have they reduced supply or demand? Has criminalizing thousands of people lowered consumption or violence? Decades of prohibition suggest the opposite. These tactics haven’t solved the problem—they’ve only deepened it.

A question of image.

Behind the proliferation of canine units lies not only a desire for revenue, but also a political imperative: to show that action is being taken. Many local police departments claim that drug-sniffing dogs serve as a powerful deterrent. However, the presence of these units does not prevent drug use. At most, it displaces it—to other substances, or to more private, less visible settings, often increasing the risks for users.

For example, moving consumption from public spaces such as parks and plazas to more secluded areas may help reduce the perception of insecurity. And that perception is often enough. A significant portion of the public supports these units without questioning whether a greater sense of safety actually corresponds to reduced crime. This raises a fundamental question: do canine units truly reduce crime, or do they simply improve the feeling of control?

The use of drug sniffer dogs also serve another function: improving the public image of police officers on the street. These animals spark curiosity, sympathy, and even affection, and they enjoy broad social acceptance. As Fran Martín, a local police officer in Vilafranca del Penedès, put it: “I’m very happy, because people now come up to me; they approach us. I seem friendlier. Even though the dog is just another tool for our work, it gives us a much more approachable image.” (Eix Diari, 2017). However, it’s worth looking at the experience of those who have already gone down this road. In the UK, the British Transport Police, after noting that most dog-led searches were unsuccessful, acknowledged that these operations were damaging public trust. As a result, they significantly scaled back their use of detector dogs.

Have you come across a canine unit?

As you can see, the situation of canine units in local police forces in Spain is as irregular as it is disconcerting. But, beyond the legitimacy of the use of these detector dogs in public spaces, the stories of Araceli, Laura, Alberto and Pablo make it clear that they are a tool for the control and persecution of substance users who pose no threat to public safety.

Therefore, if you have been unlucky enough to come across a municipal canine unit, whether they have found substances on you or not, LEAP encourages you to denounce the situation by filing a complaint with the city council, the police station itself or the Ombudsman. And if you want to file allegations, in this article you will find some key points to request the nullity of the canine action. Only in this way will it be on record that safety cannot be an excuse to sacrifice freedom and curtail our rights.

Acknowledgements: Amber Marks, Juan José Perea and Fran Azorín.

Núria Calzada is a drug policy reform advocate and harm reduction educator, currently leading research and education initiatives at Kykeon Analytics. She is also a member of LEAP Europe and collaborates with Cáñamo Magazine, conducting interviews on drug policy around the world.